This is an old revision of the document!

IEMT Treatment Plans

For clients facing complex mental health, emotional and psychological challenges

A treatment plan is a set of written instructions and records pertaining to the treatment and management of a mental health condition and/or crisis. A treatment plan should include the client’s key personal information, the diagnosis and/or presenting problem, an outline of the treatment under consideration, expected and intended outcomes, and the measurement of these outcomes during, and at the conclusion of, treatment.

A treatment plan should include:

- A definition, qualification, and quantification of the presenting problem

- A description of the treatment proposed by the coach/therapist

- A timeline for treatment, including frequency and duration of sessions

- Identification of the major treatment goals in the SMART format

Whilst for many clients a treatment plan is not necessary there are many scenarios and presenting problems for which a treatment plan will offer an opportunity for the client to collaborate in their treatment and to provide a structured framework for treatment. Many clients with complex issues and who may be new to therapy/treatment may find this reassuring, professional and motivating.

Where the appropriate permissions exist the treatment plans may be shared with mental health professionals and community support teams in order to increase multi-disciplinary communication, cooperation, and collaboration.

IEMT Practitioners should consider a treatment plan in the following scenarios:

- Clients experiencing serious mental illness or distress

- Clients experiencing multiple issues affecting them emotionally, physically, socially, and psychologically

- Clients with serious physical health issues

- Clients engaged in the criminal justice system

- Clients under compulsory treatment orders

- Clients engaged with multiple care/support/treatment agencies

- Clients referred by employers

- Working with teenagers and/or their families

- The vulnerable elderly

- Clients with developmental disabilities and/or intellectual challenges

- Clients experiencing sexual orientation or gender identity issues

- Clients who are being bullied and/or abused and/or exploited

- Clients with little socio-economic resource, minimal opportunities, and poor prospects

Each treatment plan is unique to each individual though many similarities and recurring themes will undoubtedly arise over time.

Contents of a Treatment Plan

All treatment plans are specific to each client. They are the collaborative result of the discussions and agreements that exist between the coach/therapist and the client.

Differences in the care plans between different clients are most likely to manifest in any or all of the following components:

- Demographics and personal history

- Assessment/diagnosis – whilst many people may share the same diagnosis, the experience of the client will be unique as will the context in which the presenting problem/illness/distress occurs

- The presenting problem – i.e. the problems or symptoms that initially brought the client to treatment

- Existing resources – the pre-existing resources that the client brings to treatment. These will be either intrinsic (i.e. clients own strengths and characteristics) and extrinsic (i.e. family support, financial aid, social support)

- Treatment contract – the agreement between the therapist and client that summarises the intentions of treatment

- Responsibilities – a section on who is responsible for which components of treatment, including the coach/therapist and other agencies across the multi-disciplinary and community support agencies

- Treatment outcomes – what are the intended and expected outcomes of treatment

- Specific interventions – the techniques, exercises, and interventions deployed by the coach/therapist

- Session frequency, duration, and number

- Progress/outcomes – the ability, rate, range, and degree of therapeutic progress will vary enormously between clients

Behavioural Observations

Note behavioral observations of the client's presentation of self. The coach/practitioner should assess the client's overall mental state which involves observing their physical appearance and interactions with others.

The coach/practitioner should also assess the client's overall mood (i.e.sad, angry, indifferent) and overall affect (range, scope, and articulation of emotional expression). These observations assist the coach/practitioner in making an effective diagnosis and developing an appropriate treatment plan.

Examples of observations that constitute the mental status exam include:

- Orientation to time, date, and place

- Self-grooming and hygiene (also observe fingernails, breath, odour, the freshness of clothing, etc)

- Eye contact - avoidant, little, none, or normal

- Mood - angry, withdrawn, irritable, tearful, anxious, depressed, etc

- Affect - appropriate/inappropriate, labile, stoical, blunted, flat

- Thought content disturbances - i.e. delusions, hallucinations, obsessions, intrusions, suicidal thoughts

- Behavioral disturbances such as aggression, poor impulse control, unreasonable demands

- Motor activity - agitation, calm, restless, rigid

- Speech (volume, speed, coherence)

- Interactional style (i) - i.e. nervous giggling, bombastic, cooperative, erratic

- Interactional style (ii) - active participant, passive, failure to initiate, conversationally domineering, etc

- Intellectual functioning (impaired, unimpaired)

- Memory - short term, long term

- Perceptual disturbances - i.e. hallucinations, the agency of communication and meaning

- Attention span - ability to focus and concentrate

Assessment Tools

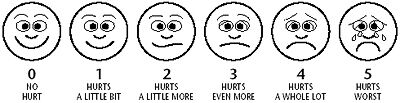

Assessment tools are standardised systems and processes that facilitate the qualification and quantification of specific conditions, disorders, experiences, and problems. Tools include scales, charts, checklists, graphic presentations, and structured interviews. These need to be suited to the client under assessment, culturally sensitive to the context in which they are used, reliable and valid if they are to inform professional judgment and opinion.

Examples of commonly used assessment tools

1. Anxiety

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7)

- Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)

- Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

2. Depression

- Geriatric Depression Scale

- The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale

3. Addiction

- Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

- Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)

- South Oaks Gambling Screen Assessment

- Brief Addiction Monitor

- Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)

4. Trauma

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

- The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale

5. Behavioural

- Wahler Self-Description Inventory

- Daily Living Activities

- Parental Stress Scale

6. Pain

- Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

- Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS)

- Adult Non-Verbal Pain Scale (NVPS)

- Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD)

- Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS)

- Critical-Care Observation Tool (CPOT)

Targets, Goals and Outcomes

To evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment plan, the coach/practitioner needs to track the client's progress and measure the efficacy of treatment and interventions. In some instances, it may be beneficial to ask the client to keep track of their inner experiences and behaviours in a log, chart, or diary so that progress can be monitored.

People in treatment are more likely to complete objectives when the goals are personally important to them, thus all goals should add value or meaning to the client's situation.

“People are not lazy. They simply have impotent goals—that is, goals that do not inspire them.” — Tony Robbins

“If you want to live a happy life, tie it to a goal, not to people or things.” — Albert Einstein

SMART Goals

All outcomes, aims and treatment goals should be measurable using the SMART criteria:

- Specific – target a specific area for improvement. (what)

- Measurable – quantify or at least suggest an indicator of progress. (how much)

- Assignable – specify who will do it. (who)

- Realistic – state what results can realistically be achieved, given available resources. (why)

- Time-related – specify when the result(s) can be achieved. (when)

The term S.M.A.R.T. Goals and S.M.A.R.T. Objectives are often used. Although the acronym SMART generally stays the same, objectives and goals can differ. Goals are the distinct purpose that is to be anticipated from the assignment or project, while objectives, on the other hand, are the determined steps that will direct the full completion of the project goals. (SAMHSA Native Connections. ”Setting Goals and Developing Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound Objectives“ (PDF). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.”)

Two additional criteria create the SMARTER system:

- Evaluate - The sixth step in goal setting using the S.M.AR.T.E.R. method is to ensure that all progress towards each goal is evaluated.

- Readjust - The seventh step is to adjust treatment according to the evaluation.

Discussion

“The popularity of SMART goals is understandable – they seem simple, memorable and easy to use. But there’s a major catch – the research literature suggests that, in many contexts, they simply don’t work very well: in fact, they can even be detrimental.” https://psyche.co/ideas/so-called-smart-goals-are-a-case-of-style-over-substance