Procedure Manual for IEMT and MVF Training

1. Introduction

Purpose of the Manual

This manual equips clinicians with comprehensible instructions on the correct delivery of the Integral Eye Movement Technique (IEMT) in psychological trauma and the correct use of Mirror Visual Feedback (MVF) in treating phantom limb pain. Nothing contained here is intended to replace conventional treatment services and applications nor to portray the methodology as superior to other methodologies.

Overview of IEMT and MVF

Integral Eye Movement Therapy (IEMT) is a psychotherapeutic approach designed to alleviate emotional distress and identity-based issues through specific eye movement techniques. It focuses on reducing the emotional intensity of memories and imprints that influence current emotional well-being. The therapy is particularly geared towards addressing patterns that perpetuate problems, effectively helping clients reframe their emotional experiences and identities. IEMT's techniques involve observing and altering eye movements to reprocess traumatic or intense emotional memories, thereby promoting psychological healing and behavioural change.

Mirror Visual Feedback (MVF) is a therapeutic technique utilized in treating phantom limb pain, where patients use a mirror to create the illusion of the presence of their amputated limb. This visual feedback helps the brain reconcile the discrepancy between the perceived and actual physical body, reducing pain and discomfort associated with phantom sensations. MVF is effective in retraining the brain and can significantly alleviate pain by modifying neural pathways related to the missing limb's sensory and motor signals.

Organisation of Training and Delivery

- Role: Guides and advises the Trainer and Director for the Project.

Andrew T. Austin - Trainer and Director for The Project

- Role: Responsible for the overall direction and training within the project. Acts as the primary liaison between the Advisory Board and the Core Training Group.

Core Training Group (Association Members)

- Composition: Includes both Clinical and Non-Clinical Association Members.

- Role: Receives training from the Director and is responsible for cascading the knowledge and training to the NGOs, charities, and clinicians in the field.

NGOs, Charities, and Clinicians Working in The Field

- Role: Apply the training to deliver treatment and services to the patients under the project's scope.

Patients

- Role: The recipients of the medical treatments and services provided by the trained staff of NGOs, charities, and clinicians.

This structured layout ensures that guidance and training flow effectively from the top-level Advisory Board down to the patients, optimizing the quality and consistency of medical care provided.

2. IEMT for Trauma

==== Module 1: Introduction to Eye Movements ==== * Eye Movement Fundamentals * Practical Exercise: Directing Eye Movements

Introductory Exercise in IEMT Training

Overview

During Integral Eye Movement Therapy (IEMT) training sessions, participants engage in a role-playing exercise designed to simulate and practice therapy techniques. The exercise involves participants pairing up, with one person playing the role of the therapist and the other as the client.

Objective The goal is to practice eye movement techniques central to IEMT, ensuring participants are prepared to guide clients through these movements effectively.

Procedure Participants instruct each other to move their eyes in specific patterns: six times left, six times right, and six times along each diagonal direction. It's crucial for the client to continually think of a specific memory, particularly one that invokes a strong emotional response, ensuring simultaneous engagement in eye movement and memory recall.

Role Reversal After practicing one round, participants switch roles. This role reversal allows each person to experience and understand the therapy's challenges and nuances from both the practitioner's and the client's perspectives.

Follow-Up Questions After the exercise, the practitioner inquires if the client can revert the memory to its original state. If the client struggles, they are encouraged to “try harder.” This interaction is designed to challenge the client's ability to dissociate from the problem memory, addressing one of the patterns of chronicity in therapy.

Kinesthetic Reduction and Dissociation The session emphasizes reducing the kinesthetic feelings associated with memories. The aim is to decrease the emotional intensity tied to the memory, making it feel more distant and less vivid. This process is indicative of a dissociative shift, helping clients view the memory as a detached, historical event rather than a relived experience.

Patterns of Chronicity The exercise addresses chronic patterns where clients continuously test for evidence of their problems while ignoring any improvements. This pattern is often reinforced in clinical settings, where the focus remains on negative outcomes despite significant progress.

Learning Outcome This introductory exercise is designed to lay a practical foundation for managing basic eye movement techniques in therapeutic settings. It also helps participants become sensitive to the emotional aspects of therapy. The session prepares them for more advanced topics in the training, including a deeper exploration of trauma and its kinesthetic manifestations.

Module 2: IEMT Kinaesthetic Pattern

Understanding Kinaesthetic Pattern Questions

The Kinaesthetic Pattern (hereafter, “The K-Pattern”)

Elicit the undesired state (whole being) or kinaesthetic expression (part body feeling)

- Ask the client to assign an amplitude scale (1 – 10). “…and out of ten, how strong is this feeling, with ten being as strong as it can be?”

- Ask: “…and how familiar is this feeling?”

- Ask: “…and when was the first time that you can remember feeling this feeling… now… it may not be the first time it ever happened, but rather the first time that you can remember now…”

Allow the client 20-40 seconds to access the imprinting event. Do not offer guidance or advice and allow the client to perform his or her own kinaesthetic transderivational search.

- When the client has accessed their earliest recollection, ask, “…and how vivid is this memory now?”

Instruct the client to hold that memory vividly in their mind for as long as possible…

Guide the client in performing eye movements through the different access points. Periodically reminding the client that “…and if this memory fades, try very hard to bring it back…try as hard as you can to retain that experience…”

Continue until the client protests that they cannot retain or recall visual memory, or for a maximum of 40 seconds, which occurs soonest.

- Test 1. Ask, “…and how does that memory feel now…?”

- Test 2. Ask, “…and what happens when you try to access that feeling now?” If the imprint event still triggers negative kinaesthetic, repeat the process.

Test 3 (optional). Ask: “…and when you think about event now, what feeling comes up for you now?”

If a negative kinaesthetic emerges, then repeat the basic process and locate the next imprint.

Techniques for Professional Delivery

Using as few words as possible and keeping strictly to the script is essential, and it is important not to get sidetracked by side issues, chit-chat, and rapport-building, as this can be counterproductive to the overall approach.

Some general guidelines in delivery:

- Sit opposite but slightly off-centre from the client. When guiding the eye movements, your finger should be around 18 inches from the patient's face.

- An upward-pointed finger, or pen, is better than using a “pointing finger” that points directly at the client.

- The movement speed will be around 1 second per left-right-left sweep (“double sweep”). This can be slowed a little for a client who demonstrates slower processing, as revealed in their communication style, kinetic movements, etc, i.e. slower speech and overall bodily movement.

- It is important that the finger sweeps are broad enough to move the eyes to their peripheries.

Module 3: Addressing PTSD

The Lynchpin

In the context of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), practitioners must be versed in both the diagnostic criteria and therapeutic modalities. The “lynchpin” concept is integral to understanding and addressing PTSD, particularly within the framework of Integral Eye Movement Therapy (IEMT).

The lynchpin, a central tenet in IEMT, refers to a pre-trauma personality characteristic that was previously inconspicuous but has become a key causative factor in the individual's PTSD following a traumatic event. This once innocuous trait now serves as a catalyst, triggering intense and distressing flashback experiences when the individual encounters similar contexts or experiences that involve this trait.

Addressing the Lynchpin

The common thread in PTSD is the attempt to retroactively alter the past or revert to their pre-trauma selves, hoping to change the outcome and seeking understanding from others. Unfortunately, while the focus is often on the aftermath, the internal struggle to amend a perceived fault goes unnoticed. This pattern is crucial to identify as it forms the basis of the therapeutic intervention.

It is essential to discern true PTSD, which aligns with the DSM-5 criteria, from conditions that may superficially resemble it but do not fulfil the formal diagnostic requirements. This distinction underscores the need for precise clinical evaluation and avoids conflating self-diagnosed PTSD with that which is clinically established.

In therapeutic practice, patients often desire to return to their pre-trauma selves and seek empathy from others, sometimes through public awareness efforts. The lynchpin concept facilitates a deeper understanding of the patient's experience by focusing on the internal changes they have undergone rather than external circumstances.

During the IEMT training, practitioners learn to identify and address the lynchpin using targeted eye movement techniques to mitigate its influence on the patient's current experiences. A reported shift in emotional response, perspective, or a sense of psychological progress often accompanies this process.

Furthermore, the training delves into the “living dead metaphor,” which encapsulates the feeling of being emotionally detached or numb, as if one were merely existing rather than truly living. The metaphor provides a framework for practitioners to explore and modify the patient's trauma narrative, potentially reducing its emotional impact.

Medical professionals receiving this training will be equipped to not only identify the lynchpin in PTSD patients but also to employ IEMT strategies effectively to alleviate the profound effects it has on their lives. This includes adjusting the “edit points” of traumatic memories to disrupt their recurrent and debilitating nature.

Understanding the Lynchpin: A Structural Approach for Identification in PTSD Patients

1. Introduction to the Lynchpin Concept:

- Definition of the lynchpin in relation to PTSD.

- The significance of distinguishing between a normal personality trait and its transformation post-trauma.

- Overview of the lynchpin's role in maintaining PTSD symptoms.

2. Analyzing the Traumatic Timeline:

- Differentiating between 'self' (internal factors) and 'other' (external factors beyond the patient's control).

- Dividing the patient's experience into segments: before the event, during the event, and after the event. This is not performed directly on the client's experience but rather through the use of hypothetical or real examples that illustrate the process.

3. Uncovering the Lynchpin:

- Isolating the specific moment or trait behaviour that the patient fixates on via story examples.

- Recognizing how this previously normal trait has become a source of distress and a trigger for flashbacks.

- Understanding the patient's tendency to cyclically attempt to correct this trait in the hope of negating the traumatic event.

4. Clinical Illustration Through Case Stories:

- Providing detailed narratives that exemplify the lynchpin identification (as shown in the provided stories below).

- Highlighting the pivotal moment or behaviour that becomes the lynchpin for the patient's PTSD.

5. Therapeutic Intervention:

- Initiating Integral Eye Movement Techniques to address the identified lynchpin.

- Guiding the patient through recognizing and reframing the lynchpin to reduce its hold over their current life.

6. Feedback and Follow-up:

- Encouraging patients to articulate their experiences post-intervention.

- Observing any shifts in emotional response or behavioural changes.

- Repeat the process where necessary to ensure the lynchpin's influence is diminished.

7. Broader Implications of the Lynchpin

- Discussing how the lynchpin influences the patient's identity across various contexts.

- Addressing the need for understanding from others and the frustration when it is not met.

- Explaining how the lynchpin can infiltrate multiple aspects of the patient’s life due to its association with their identity.

8. Conclusion:

- Summarizing the importance of identifying the lynchpin in the therapeutic process.

- Emphasizing the role of the practitioner in facilitating a recontextualization of the lynchpin to promote healing and recovery.

Story Examples

Preframe

I'm uncertain of the extent to which I can assist you. While I'm able to work with you, the exact benefits remain to be seen as the possibilities are numerous. The initial step is to gain an understanding of your situation, which is evidently quite severe. My intent is to guide you through a specific evaluation to see if it resonates with your experiences. This is crucial for my comprehension of your case.

Story 1: A Case of PTSD Consider this scenario: a man suffering from PTSD. (Here, you would show or draw the timeline diagram). Picture this as a timeline. Your current position is here, and the traumatic event is there. (Break down the timeline into sections: before, during, and after the event). Here's what happened before the event, the event itself, and what's happening now.

Above the line is 'self'—his experiences, decisions, and actions. Below the line is 'other'—aspects he has no control over, such as other people and the environment.

This individual was returning home from a party and was attacked. It was a case of senseless violence; he was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

We examine his actions before the incident—leaving the party, deciding to walk home against his friends' advice to take a taxi, thinking it necessary to sober up for an early shift the next day.

We speculate on the perpetrators—likely indulging in drugs and alcohol, habitual offenders, and generally problematic individuals.

Their lives intersected disastrously at the event. The details of their cruelty are clear—they cornered him, mocked, and assaulted him.

Post-event, what he couldn't control was the media attention, family reactions, and hospital gossip—all of which he overheard in an open ward.

Afterward, he withdrew from social life, turned to alcohol and drugs, and lived in isolation for a decade.

The critical revelation is what he fixates on—it's not the event itself, but the moment he pleaded for his life that haunts him.

Story 2: The Beirut Port Explosion Another example involves a man who worked at the Beirut port. On vacation with his girlfriend, he agreed to extend the trip at her request. His friend covered his shift, which fell on the day of the catastrophic explosion. The friend perished, and the man, now jobless, descended into isolation and depression.

He didn't flashback to the phone call or losing his job but to the moment he agreed to stay with his girlfriend because it made her happy.

These individuals relentlessly scrutinize their actions. What was once a normal behavior becomes the focus of their rumination, as though changing that trait could have averted the catastrophe.

This relentless self-interrogation about a normal behavior or trait is what exacerbates their PTSD. It infiltrates their identity, affecting multiple life contexts, making them believe that this very aspect of who they are caused the traumatic event.

Module 4: IEMT Application for Pain

Pain Pathways and Types of Pain

Pain is a complex sensory and emotional experience that plays a critical role in protecting the body from harm. Understanding the pathways through which pain signals are transmitted to the brain is essential for clinicians managing trauma and combat injuries.

Types of Pain Signals

Pain signals are initiated by nociceptors, specialized sensory receptors that detect damage or potential damage to tissues. These signals are primarily of two types:

- Nociceptive Pain: This occurs when nociceptors are stimulated due to injury to bodily tissues. It is the pain that arises from physical damage such as cuts, fractures, burns, or inflammation.

- Neuropathic Pain: This type of pain is a result of damage to the nervous system itself, which can alter pain perception. It might be experienced as a burning, shooting, or stabbing sensation.

Transmission of Pain Signals

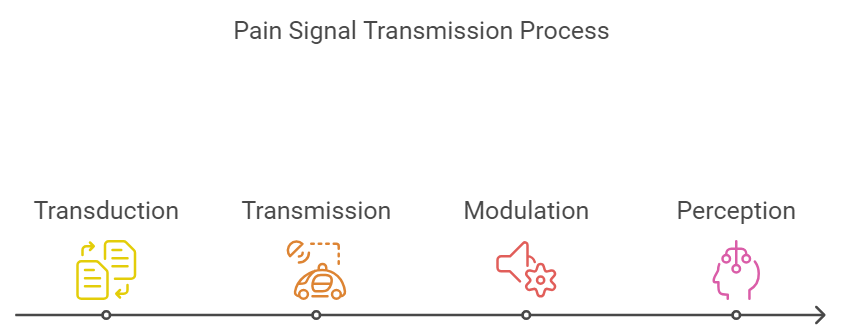

The process of pain signal transmission involves several steps:

- Transduction: The conversion of traumatic or chemical stimuli into electrical signals at the site of damage.

- Transmission: The pain signal is carried from the nociceptors through peripheral nerves to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

- Modulation: At the spinal cord, neurotransmitters can either amplify or dampen the pain signal.

- Perception: The brain interprets these signals as pain, influenced by both physical and psychological factors.

Types of Pain

Understanding different types of pain is crucial for effective management, especially in a setting involving war trauma and combat injuries.

- Acute Pain: Immediate pain resulting from injury, lasting less than six months. It serves as a warning mechanism.

- Chronic Pain: Persistent pain that lasts longer than six months and can continue even after the injury has healed.

- Burn Pain: Burn pain is typically acute and intensely painful due to nerve damage. It requires immediate pain relief and long-term management.

- Crush Injuries: Can result in both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Initial severe pain may transition to chronic pain syndromes if nerves are damaged.

- Visceral Pain: Originates from internal organs; often difficult to localize. Typical in blunt force trauma to the abdomen.

- Somatic Pain: It arises from skin, muscles, bones, and joints. It is more localized and caused by direct trauma.

- Referred Pain: Pain felt in a part of the body other than its source, which is important for diagnosis.

- Phantom Limb Pain: This occurs after amputation, and the pain is felt as though it comes from the amputated limb.

- Psychological Pain: Emotional distress that exacerbates physical pain symptoms, requiring holistic care.

- Inflammatory Pain: Signifies tissue damage and inflammation sustained by biochemical substances.

Gate Control Theory of Pain

The gate control theory of pain, proposed by Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall in 1965, is a revolutionary theory that provides a new framework for understanding the mechanisms of pain perception and modulation. This theory challenges the traditional view of pain as a simple sensory experience. It introduces the concept of a “gate control system” that regulates the flow of pain signals to the brain.

Overview of the Theory

The gate control theory proposes that pain signals from the periphery (e.g., skin, muscles, organs) are modulated by a “gate” mechanism in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This gate can either facilitate or inhibit the transmission of pain signals to higher brain centres, depending on the interplay of various factors. The key components of the gate control theory are:

The gate control system: A functional unit located in the spinal cord's dorsal horn that regulates pain signals' flow. Afferent fibres: Sensory nerve fibres carry pain signals from the periphery to the spinal cord.

Small-diameter, slowly conducting fibres (C-fibers) transmit dull, burning, and chronic pain signals. Large-diameter, rapidly conducting fibres (A-beta fibres) transmit sharp, localized pain signals and non-noxious stimuli like touch and pressure.

Descending fibres are nerve fibers that originate in the brain and descend to the spinal cord, modulating the gate control system.

Mechanism of Gate Control

According to the theory, the gate control system functions as follows:

Pain signals from the periphery travel through the afferent fibres (both C-fibers and A-beta fibres) to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The gate control system in the dorsal horn can either allow or block these pain signals from reaching the brain. The activity of the gate is modulated by the relative activity of the afferent fibres:

Increased activity in the small-diameter C-fibers tends to open the gate, facilitating the transmission of pain signals to the brain. Increased activity in the large-diameter A-beta fibres tends to close the gate, inhibiting the transmission of pain signals to the brain.

The descending fibres from the brain can also influence the gate control system, either facilitating or inhibiting the transmission of pain signals.

Implications and Applications

The gate control theory provided a new understanding of pain modulation and had several important implications:

It explained how psychological factors, such as attention, emotion, and past experiences, can influence pain perception by modulating the descending fibres that control the gate. It provided a theoretical basis for non-pharmacological pain management techniques, such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), which activates the large-diameter A-beta fibres and can close the gate, reducing pain perception. It highlighted the importance of considering both the sensory and emotional components of pain, leading to the development of multidisciplinary pain management approaches.

While the gate control theory has been refined and expanded upon over the years, it remains a fundamental theory in pain research. It has contributed significantly to understanding pain mechanisms and developing effective pain management strategies.

Management Implications

Effective pain management must be tailored to the type of pain and its underlying cause. This involves:

- Immediate and adequate analgesia for acute pain.

- Monitoring and treatment adjustments to prevent the transition from acute to chronic pain.

- Rehabilitation strategies to address physical and psychological aspects of pain perception and management.

Application of IEMT Techniques to Pain Management

In many, but not all, instances, chronic pain can be reduced by applying the IEMT K-Pattern to the pain experience. The session frame set for the client mustn't lead them to expect adequate analgesia or anaesthesia regarding their pain experience. The practitioner must avoid the temptation to enquire if the pain is reduced or even how it compares to before the session.

It should be noted that this method is of little value in treating acute or chronic phantom limb pain.

The IEMT method exploits the principle that pain, by its very nature, is designed to grab one's attention. By de-potentiating the supporting psychic structures of the pain experience, over time, less attention is given to it. There is nothing in this work that is to replace or substitute conventional medical pain management protocols and practices.

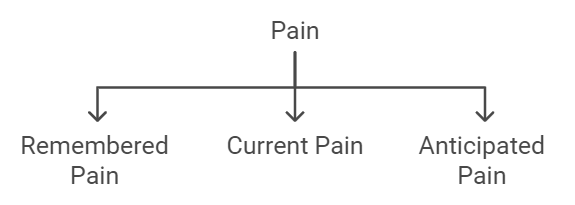

Regarding pain, there are some dimensions to consider:

- The pain that is remembered

- The pain that is current

- The pain that is anticipated

In addition, the practitioner needs to consider the response to the pain, which may be adaptive or maladaptive. Pain leads to suffering, and in some instances, alleviating the pain does not necessarily change the experience of suffering, depending on how the person has adapted to it. Alcohol and drug use, self-harm, social withdrawal, self-pity, etc, may continue long after pain has been alleviated.

An example of the K-Pattern as applied to pain will look like this:

- “On a score out of ten, with ten being as strong as it can be, how strong is the pain now?” (or, “as you remember it?”, “anticipate it to be?”)

- “And, how familiar is this pain?”

- “And when is the first time you can remember experiencing this feeling of pain? It may not be the first time you have experienced it, but it is the first time you can remember now.”

- “And how vivid is this memory?”

Then, the client is instructed on eye movements while mentally holding on to that memory.

3. Application of Mirror Visual Feedback (MVF)

Part 1: Pre-Assessment

The pre-assessment process is not a substitute or alternative to any prior medical assessment but rather assesses the likelihood that the MVF process will be the best choice for the patient with phantom limb pain. The principles outlined here are not exact nor universal, as there will be counterexamples to the generalisations offered here. Experience has shown that prior failure with MVF does not necessarily mean that MVF won't work for that individual, but may well just indicate the delivery of MVF was carried out erroneously.

Mirror Visual Feedback will be most likely to be effective when the following criteria are met:

- The phantom limb image is distorted from a healthy limb image. This may be a gross injury retained in the limb image, phantom contractures, or abnormal positioning.

- The limb is mobile. This mobility may be willed or involuntary.

- The limb image changes when pain occurs.

- Sensorial “remapping” has occurred - hands to face/neck, lower limb to genital area.

Mirror Visual Feedback will be less likely to be effective when:

- The limb image is normal.

- The phantom has no movement.

- No sensorial remapping has occurred.

- The limb image is fixed and unchanging, even when pain occurs.

The length of time that the person has suffered phantom limb pain appears to have no relationship to the outcome.

Part 2: Assessing the Phantom

Initial Patient Assessment

In the context of phantom limb pain, a comprehensive initial medical assessment is crucial. Typically, patients will have undergone detailed evaluations to establish an accurate diagnosis. However, clinicians must know that some individuals might be “poor historians” for various reasons. They may agree with the examiner's suggestions without critical reflection due to a desire to please, may lack insight into their symptoms, or find it challenging to articulate their physical sensations. These factors can complicate the diagnostic process.

Phantom limb pain is pain that feels like it's coming from a body part that's no longer there. Clinicians should recognize that this condition is not monolithic but potentially multifactorial with overlapping pain types:

- Neuromas: Nerve endings at the amputation site may form neuromas, which can become painfully sensitive.

- Stump Pain: Pain at the amputation site can arise from various sources, including skin irritation, muscle spasms, and bone pain.

- Bone Pain: Can be due to bone spurs or other irregularities at the amputation site.

- Psychogenic Pain: Sometimes, the pain may also have psychological contributors, reflecting the complex interplay between mind and body post-amputation.

These various pain experiences might coexist, making it critical not to view the patient's condition through a binary lens of “either/or” but rather consider a “both/and” scenario in which multiple factors may contribute to the pain.

So, the scenario may arise that a person has a phantom limb that is otherwise pain-free, but the neuroma pain projects into it. In this instance, the MVF treatment is unlikely to be productive.

Part 3: Stages of the Treatment Session

The patient progresses through eight observable stages when using the mirror box. These are:

- Stage 1: Patient expectations and anticipation

- Stage 2: Focus of attention

- Stage 3: Reaction and Abreaction

- Stage 4: Emotional reunion with limb image

- Stage 5: Abreactional states

- Stage 6: Fascination and Exploration

- Stage 7: Fatigue

- Stage 8: Telescoping phenomena

Stage 1. Patient expectations and anticipation

The patient unfamiliar with MVF use will likely have their preconceptions of what will follow in terms of the experience and the clinical outcome. It should be noted that patients with the most amount of distress and the most to gain may be apprehensive and fearful that the method will be ineffective, and clinicians should note that the greater the distress, the greater the level of disappointment and added distress will be in the event of MVF proving to be ineffective.

Clinicians should seek to ascertain and neutralise the patient's expectations, regardless of their beliefs and expectations. The attitude to foster is that of, “We are finding out what is possible with this process” rather than, “This is a treatment for your condition.” Discussion of outcomes should also be avoided other than to offer that “outcomes are largely irrelevant at this stage, as we are simply exploring what is possible.”

For the client who is sceptical and dismissive of the MVF approach, especially if they have tried it previously without positive effect, a neutral approach of “let's find out what happens when we change a few things around” is best rather than engaging in disagreement with the patient.

Clinicians should use a “pace, pace, pace and lead” approach, which begins by agreeing with the patient and leading them towards a more neutral stance.

Stage 2: Focus of attention

The patient is directed to create a convincing illusion by carefully adjusting the position and attitude of the limb reflected in the mirror. They are told to take as much time as needed. It will be noticed that the majority of patients find themselves quickly absorbed into the processes, and it is at this juncture, the clinician is best able to remain silent and out of view of the patient. Once patients focus on the illusion, they explore it and spontaneously create movements with their limbs.

For the outside observer, it may well appear that not much is happening, and all they can see is a patient staring at a mirror reflection of their limb. However, a lot is going on and being processed for the patient who is absorbed into the experience. This must not be interrupted.

Stage 3: Reaction and Abreaction

Shock, surprise, disbelief, and indifference are commonly experienced and expressed at this stage. For the patient who is absorbed in their focus of attention and also expresses indifference, clinicians should be aware that this may be as much of a need to “save face” as it is genuine. The clinician must remain indifferent to the reaction set expressed by the patient and, as much as possible, remain silent.

Some patients express surprise and quickly disengage from the mirror. In one instance, the patient, visibly shaken from his brief interaction with the mirror, requested leave to go outside for a cigarette. The clinician just gave a silent nod, and the patient later returned and continued his interaction with the mirror of his own volition and without the clinician's direction.

Stage 4: Emotional reunion with limb image

This stage quickly follows the reaction and abreaction stage and is commonly marked by a verbal interaction between the patient and the mirror reflection. This stage is marked by the experience of moving from merely seeing a convincing illusion to reconnecting to a visual limb image. It should be noted that whilst most patients can visually describe their phantom limb, often in detail, their visual description is created from their proprioceptive experience of it; at this point of the MVF session, the patient is now reunited with an actual visual presentation of the limb that matches their proprioceptive experience.

Stage 5: Abreactional states

For many patients, abreactional states may appear to be relatively extreme, especially those with high levels of dysmorphic distress from the loss of the limb combined with other changes to visual appearance (i.e. facial disfigurement, scarring, loss of other body parts) and function (in war trauma, genital injury and genital loss is common with leg amputation resulting from blast injury. Injuries of this nature often result not only in amputation but also in additional issues such as colostomy and urostomy formation).

The emotions expressed by the patient at this stage are abreactions, which means they are experienced and expressed “release and relief” rather than a re-experience and recycling of them.

The abreactional phase may be brief and mild for most patients and pass quickly. Still, for patients caught in the Pain-Depression-Dysmorphic Distress Cycle with a background issue of active and concurrent PTSD, a cyclical effect may sometimes be observed with emotional release, followed by further “Focus of Attention” and “Reunion with the Limb Image” followed by further abreactional releases. In these situations, clinicians are advised to “just let the patient talk it out” and to offer minimal feedback.

Stage 6: Fascination and Exploration

The fascination and exploration phase is dominated by curiosity as the patient explores the MVF experience without complicating emotions. It has been observed that some patients will happily stay in this stage until either interrupted by external necessities—i.e., the end of session time or the clinician interrupting—or internal necessities, such as the need to use the bathroom or another cigarette. It is recommended that the patient be allowed at least 20 minutes to explore this stage. Many patients have expressed a desire at the end of the session to construct themselves a mirror box and return to this exploration as soon as possible.

Stage 7: Fatigue

Fatigue is commonly reported post-session, especially where there have been strong abreactional states. Vivid dreams and deep sleep are also commonly reported in the nights following the session.

Stage 8: Telescoping phenomena

Telescoping is the effect of the phantom limb shortening with repeated use of the mirror box. In the example of an upper limb phantom, the limb shortens from the shoulder end and not from the finger end. As the telescoping develops, the patient's phantom will be reduced to just a phantom hand coming out of the stump and, finally, just the fingertips. It is unusual for the phantom fingers to disappear completely.

Telescoping is usually not noticed until after several days of consecutive use of the mirror and often not until the clinician asks about it. Whilst telescoping might seem a little unusual to anyone else, but to the patient, it appears to be experienced as perfectly natural.

Patients whose phantom pain is primarily caused by phantom contractures who only use the mirror box occasionally in order to “release” the contracture may not experience any telescoping phenomena.

Part 4: Managing Complex Issues

The Interrelationship Between Pain, Depression, and Dysmorphic Distress

Pain and Depression Dynamics

Pain, particularly chronic pain as seen in phantom limb syndrome, is a potent stressor on mental health and can significantly increase the likelihood of depression. Chronic pain can be both physically and emotionally draining, diminishing patients' ability to enjoy life and cope with stress, which in turn elevates their risk for depression.

Conversely, depression itself can alter the body's perception mechanisms, lowering the threshold for pain. This means that those suffering from depression may experience pain more intensely and more frequently than those not affected by mental health issues. This lowered pain threshold can create a vicious cycle where pain heightens the symptoms of depression, which then exacerbates the perception of pain.

People do not get used to chronic pain and desensitise to it. Over time, the pain perception threshold lowers and sensitivity to pain increases.

Dysmorphic Distress and Its Role

Dysmorphic distress arises from a profound disruption in body image and identity following major physical changes, such as the amputation of a limb. This type of distress can significantly alter how individuals perceive themselves and how they believe they are perceived by others. The dramatic change in body image can lead to a persistent sense of identity loss and self-consciousness, which feeds into both depressive symptoms and the experience of pain.

In this context, dysmorphic distress acts as a bridge that intensifies the reciprocal relationship between pain and depression. Individuals struggling with their altered appearance may experience increased pain sensitivity as their mental distress heightens their physical sensations. Similarly, the ongoing struggle with pain can deepen feelings of depression due to changes in body image and functionality.

Catharsis Through Abreaction in Mirror Box Therapy

One therapeutic approach that has shown promise in disrupting this cycle is the use of mirror box therapy. This method provides a form of catharsis through abreaction, a psychological process where patients relive and express emotional turmoil. In the context of mirror box therapy, patients can confront and reprocess the emotional distress associated with the visual and physical absence of their limb.

The mirror creates a visual illusion of the missing limb, which can help reconcile the brain's internal map of the body with its physical reality. This reconciliation can significantly reduce phantom limb pain and, by extension, the depressive symptoms and dysmorphic distress associated with it. The cathartic release obtained through this visual and emotional re-experience allows patients to interrupt the cycle of pain and depression, potentially stabilizing their emotional and physical well-being.

4. Appendices

A: Recommended Resources

- “Phantom Limb Pain: A Case Study and Review” by K. L. Jensen - Discusses the mechanisms and management of phantom limb pain post-amputation.

- “The Challenge of Pain” by Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall - Explores the complex nature of pain, including neuropathic and chronic pain.

- “The Sensory Homunculus: Anatomy of a Neurological Concept” by Penfield and Rasmussen - This foundational work explores the sensory and motor representations of the body in the brain.

- “Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain” by Mark Bear, Barry Connors, and Michael Paradiso - Offers detailed insights into the homunculus and its relation to sensory processing and phantom limb pain.

- “Phantom Limbs and the Neuroplasticity of the Brain” by V.S. Ramachandran - Discusses the role of the homunculus in the perception of phantom limb sensations.

- “Pain and Brain: Chronic Pain, Phantom Limb Syndrome, and Neural Plasticity” by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran - Covers neural mechanisms behind phantom limb pain.

- “Coping with Limb Loss” by Ellen MacKenzie - Focuses on psychological adaptation and coping mechanisms post-amputation.

- “Phantom Limb: From Medical Knowledge to Folk Understanding” by Robert G. Frank - Explores the psychological impact of phantom limb syndrome.

- “Psychological Aspects of Amputation and the Stump” by Hugh Watts - Discusses the mental health challenges faced by amputees, including depression, anxiety, and body image issues.

- “Amputation and Prosthetics: A Case Study Approach” by Bella J. May - Includes sections on the psychological adjustment to amputation.

- American Chronic Pain Association - Website - Provides resources on managing chronic pain, including phantom limb pain.

- Amputee Coalition - Website - Offers comprehensive resources on coping with limb loss, including mental health support.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) - Article on Phantom Limb Pain - Provides detailed information on the neurological aspects of phantom limb pain.

- Mind.org.uk - Mental Health and Amputation - Offers resources for mental health issues specific to amputees.

B: References

Austin, Andrew, T. (2015). Integral Eye Movement Therapy. In Neukrug, Edward S. (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Theory in Counseling and Psychotherapy (pp. 539–541, 718). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1452274126

Richards, S. (2021) Integral Eye Movement Techniques - The Definitive Guide. Integraleyemovement.com. ISBN 1838496408

Ramachandran, V. S. (1998) Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind, coauthor Sandra Blakeslee ISBN 0688172172 archive.org

Ramachandran, V. S. (2010) The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist's Quest for What Makes Us Human ISBN 9780393077827 archive.org

C: Glossary of Terms

Abreaction: Psychological process involving the reliving and expression of emotional distress, particularly effective in mirror box therapy for reprocessing emotional trauma associated with limb loss.

Amplitude Scale: A scale used to measure the intensity of a sensation or feeling, typically ranging from 1 to 10, with 10 representing the highest intensity.

Body Image Disruption: Profound alteration in self-perception following physical changes like limb amputation, leading to persistent identity loss and self-consciousness.

Bridge Effect: Dysmorphic distress acts as a link intensifying the bidirectional relationship between pain and depression by increasing pain sensitivity and exacerbating depressive symptoms.

Catharsis: Emotional release and relief achieved through expressing and reliving emotional turmoil, allowing patients to interrupt the cycle of pain and depression.

Chronic Pain: Long-lasting pain, such as in phantom limb syndrome, causing significant stress on mental health and increasing the risk of depression.

Clinical Evaluation: A comprehensive assessment conducted by healthcare professionals to diagnose and evaluate the severity of mental health conditions, ensuring accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Core Training Group: A group composed of both clinical and non-clinical members tasked with receiving training and disseminating knowledge to relevant stakeholders.

Dysmorphic Distress: Dysmorphic distress refers to a profound psychological disturbance characterized by intense dissatisfaction or discomfort with one's physical appearance. It often involves a distorted perception of body image, leading to significant emotional distress and impaired functioning in daily life.

DSM-5: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, published by the American Psychiatric Association, provides criteria for the diagnosis of various mental disorders, including PTSD.

Edit Points: In the context of IEMT, edit points refer to specific moments within traumatic memories that can be targeted and adjusted through therapeutic techniques to disrupt their recurrent and debilitating nature.

Identity Disturbance: A disruption or alteration in an individual's sense of self-identity, often observed in PTSD patients due to the impact of traumatic experiences on their core beliefs and perceptions of themselves.

Imprinting Event: The initial experience or memory associated with a particular emotional response or sensation.

Integral Eye Movement Therapy (IEMT): A psychotherapeutic approach aimed at alleviating emotional distress and identity-based issues through specific eye movement techniques, particularly effective in addressing PTSD symptoms.

Kinesthetic Pattern (K-Pattern): A technique within IEMT aimed at eliciting and addressing undesired physical sensations or feelings associated with trauma or emotional distress.

Living Dead Metaphor: A metaphorical concept describing the feeling of emotional detachment or numbness experienced by individuals with PTSD, reflecting a sense of existing rather than truly living.

Lynchpin Concept: In the context of PTSD and IEMT, the lynchpin refers to a pre-trauma personality trait that becomes a central causative factor in an individual's PTSD following a traumatic event. It triggers distressing flashback experiences when encountered in similar contexts, representing a key focus for therapeutic intervention.

Mirror Box Therapy: Therapeutic approach utilizing a mirror to create a visual illusion of the missing limb, facilitating emotional processing and reducing phantom limb pain.

Mirror Visual Feedback (MVF): A therapeutic technique used in treating phantom limb pain, where patients use a mirror to create the illusion of the presence of their amputated limb. This visual feedback helps reconcile the discrepancy between perceived and actual physical body, reducing pain and discomfort associated with phantom sensations.

NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations): Organizations independent of government involvement, typically focused on humanitarian, environmental, or social causes.

Pain Perception Threshold: The level of pain intensity required to evoke a response, which can be lowered by chronic pain or depression, leading to heightened pain experiences.

Phantom Limb Pain: Pain or discomfort experienced in a limb that is no longer present, often occurring after amputation or loss of a body part.

PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder): A mental health condition triggered by experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, and uncontrollable thoughts about the event.

Rapport-building: The process of establishing a positive and trusting relationship between therapist and client, often through empathetic communication and mutual understanding.

Retroactive Alteration: The attempt to change or amend past events, often observed in individuals with PTSD who seek to revert to their pre-trauma selves or alter the outcome of the traumatic event.

Therapeutic Modalities: Various approaches or methods used in therapy to address mental health conditions, including PTSD, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).

Transderivational Search: A process in which an individual accesses memories or experiences related to a specific feeling or sensation.

Trauma: Psychological distress resulting from a disturbing experience that overwhelms an individual's ability to cope, often leading to long-lasting emotional and psychological effects.

Vicious Cycle: A detrimental loop where pain exacerbates depressive symptoms, which in turn intensifies pain perception, perpetuating the cycle.

5. Quality Assurance

- Standards for Training Delivery

- Feedback and Continuous Improvement Processes

- Preparation of material ahead of training delivery

- Compliance with ethical guidelines

- Collaboration with the core group to ensure challenges are dealt with promptly