Table of Contents

Modal Verbs

In everyday language, words like “must”, “must not”, “should”, “should not”, “could”, “could not”, “have to”, and “need to” play crucial roles in conveying obligations, permissions, capabilities, recommendations and possibilities(choice).

In NLP these are called Modal Operators(MO) or more linguistically “modal verbs”1) or even “adverbs”. These terms can be viewed through the lens of linguistic, legal frameworks or Neuro-Linguistic Programming(NLP).

Or when explored as in Metaphors of Movement 2) or Clean language3) as boundary Metaphors themselves, e.g. must(rules) as walls – recommendations and guidelines as streets – choices as crossroads.

The goal of IEMT here is to identify problematic imprints.

Examples in Everyday Language

In everyday language, these terms help communicate different levels of obligation and advice:

MUST: Used to express a necessity or an imperative action. For example, “You must wear a seatbelt.”

MUST NOT: Used to express a prohibition. For example, “You must not smoke here.”

SHOULD: Used to offer advice or recommendations. For example, “You should see a doctor.”

SHOULD NOT: Used to advise against an action. For example, “You should not eat too much sugar.”

COULD: Used to indicate possibility or potential. For example, “You could try restarting your computer.”

COULD NOT: Used to indicate impossibility or inability. For example, “I could not find my keys.”

HAVE TO: Similar to “must”, indicating necessity or obligation. For example, “I have to finish my homework.”

NEED TO: Indicates a necessity or requirement. For example, “You need to submit the form by tomorrow.”

The legal lens: RFC 2119

RFC 21194) provides a standardized set of key words to ensure clarity and consistency in technical specifications, particularly in software and engineering contracts. These keywords denote specific levels of requirement and permission:

MUST: Indicates an absolute requirement.

MUST NOT: Indicates an absolute prohibition.

SHOULD: Suggests a recommendation, but there may be valid reasons to ignore it.

SHOULD NOT: Suggests something is not recommended, but there may be valid reasons to include it.

MAY: Indicates an optional action.

The NLP lens: NLP Modal Operators

In Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), modal operators are taught as part of the Milton Model of Hypnosis5). A more in depth review is available from Steve Andreas. He suggests that modal operators are verbs that convey necessity, possibility, choice or desire. These are divided into two main categories: Motivation and Options.

Motivation:

Necessity: Includes words like “must,” “have to,” and “need to,” which imply obligation or necessity.

Desire: Encompasses words like “want” and “need,” indicating personal desires and drives.

Options:

Possibility: Features words like “can,” “could,” and “able to,” reflecting potential and ability.

Choice: Involves words like “choose” and “decide,” highlighting options and decisions.

The dimensions suggested are Importance, Intensity, push / pull parameter of motivation.

MOs express what might be called a counterfactual state of affairs. They all indicate a situation that does not (at the moment) exist.

Verbally expressed MOs may be incongruent to the (more important) nonverbal PSACS.

For a more in depth exploration please refer to: Andreas, Steve. (2001). Modal Operators(Andreas, Steve, January, 2001)

Modal Operators and Metaphors

Metaphors often utilize these modal operators to convey deeper meanings. For example:

“The road must be taken”: The road representing direction, the “must” a rule that it has to be followed or there will be consequences (e.g. punishment). Explored these could come e.g. up as walls or fences. Obligation

“You must not let opportunities slip by”: Implies a prohibition against neglecting chances for success. Obligation

“One should always strive for excellence”: Uses “should” to recommend a general principle for living. Recommendation

“You could reach for the stars”: Choice

Practical Application in IEMT

These linguistic markers often reveal underlying beliefs and cognitive patterns that shape an individual's emotional responses and behaviors – or in IEMT terms an imprint. By paying close attention to these markers during sessions, practitioners can uncover deep-seated imprints—specific memories and emotional events that significantly influence current issues.

Traumatic experiences leave most people with strategies to avoid recurrence, which also manifest in the form of believe statements with MOs. Mostly the client is not aware of these structures and you can explore these with “What if”/“What happens”/“or else ?” questions.

I.e., repeat the clients MO statement and then “or else what happens ?”

This question can result in an associated higher emotional/traumatic, normally avoided, state. If this happens you can e.g. directly go into the K-Pattern / “Hold THAT thought and move your eyes”.

or

“So, what if you do it anyways (and go against a rule, recommendation, take a choice), and you get (embarrassed, angry, …) then what does that MEAN?”

This question points, especially if you prime it, more to an identity meta position. Peoples default is to go into cause and effect - i.e. if this, then that, also called “complex equivalence” in NLP. “Doing that means I am ….” .

If you do the second variant, you can eventually get a negative Core-Value (C-Value) statement like: Lack of value: “I'm not worthy.”, Lack of authenticity: “I'm a fraud,” “I'm fake.”, Lack of ability: “I'm no good.”, or do a lack, wants, needs and or the Patterns.

Cave: For both ways it is necessary to have a very agreeable person, high status and or good rapport unless you want to train for three stage overreactions. This isn't easy for most clients, especially if it involves very shameful emotions, you may want to use more indirect means.

With IEMT you can ask “When did you decide that?”/“When did you learn that?” If there's a memory you can do the K pattern movement or explore the identity bits of the statement

MOs indicate a situation that does not (at the moment) exist (future orientation).

MOs imply consequences when followed or not (looking back from an imagined future), extrapolated from experience (problematic imprint?)

Verbally expressed MOs may be incongruent to the (more important) nonverbal Physiological State Accessing Cues (PSACS).

MOs can lead to correspondent Three Pillar like cycles and C-Values we can explore.

Practical Application in Non Violent Communication

We are never angry because of what others say or do; it is a result of our own 'should' thinking. Marshall Rosenberg6)

From an IEMT point of view this comes close to the lacks needs wants exploration.

- “We are never angry because of what others say or do”:

From the lens of Non Violent Communication (NVC)7) this part of the quote suggests that external events or other people’s behaviors are not the direct cause of our anger. Instead, anger is a signal pointing to something deeper within us.

- “It is a result of our own 'should' thinking”:

The term ”'should' thinking“ refers to rigid, judgmental thoughts that impose expectations or demands on ourselves or others. When we believe that things “should” be a certain way, we set up a mental framework that can lead to frustration and anger when reality does not match our expectations.

How 'Should' Thinking Leads to Anger through the NVC lens

Unmet Expectations:

When we think in terms of “should,” we have specific expectations of how people or situations ought to be. When these expectations are unmet, we experience frustration and anger.

Judgmental Thoughts:

'Should' thinking often involves judgments about others’ actions (e.g., “They should be more considerate,” “He should know better”). These judgments can create feelings of resentment and anger.

Disconnected from Needs:

Focusing on 'should' thoughts can disconnect us from understanding our underlying needs. Instead of recognizing that we need respect, understanding, or cooperation, we get caught up in the belief that others are wrong for not meeting our expectations. Applying NVC to Transform Anger Using NVC, one can transform anger by:

Identifying Observations:

Separating what actually happened from our judgments about it.

Recognizing Feelings:

Understanding that our anger is a secondary emotion often masking other feelings like hurt or fear.

Uncovering Needs:

Identifying the unmet needs that are triggering our emotional response.

Making Requests:

Formulating clear, positive requests that address our needs without blaming or demanding.

Example

Suppose someone arrives late to a meeting. Instead of thinking, “They should respect my time,” which leads to anger, you could use NVC:

- Observation: “You arrived 30 minutes after our scheduled time.”

- Feeling: “I feel frustrated.”

- Need: “I need reliability and respect for my time.”

- Request: “Could we agree on a way to ensure we both arrive on time in the future?”

By addressing the situation through NVC, you shift from anger and judgment to understanding and constructive communication. This approach aligns with Rosenberg’s quote, illustrating that managing our 'should' thinking can transform how we experience and express our emotions.

In IEMT we could identify the Three Pillars, work on the imprints and offer the client strategies like NVC. This is also an interesting in terms of analysing and pointing out the interal dialog from the point of Pronouns work in IEMT.

Practical Application in Clean Language

In Clean Language(CL)8) as often reflect deep-seated beliefs and emotional states. Understanding the use of these modal operators in dialogue can help individuals identify and change their metaphors for more positive outcomes. For example:

Changing “I must not fail” to “I should try my best” reduces the pressure of absolute success and allows for learning from mistakes.

Shifting from “I could never do that” to “I should try to do that” opens up possibilities and encourages taking risks.

CL offers an exercise to directly work with statements like these:

- identify a metaphor for when you are angry and act inappropriately as a result;

- identify a second metaphor for how you would prefer to respond;

- explore how you can convert or evolve the first metaphor into the second;

- translate your insights into how you can change your behavior in your everyday life;

- rehearse this new behavior.

For a more in depth exploration please refer to: Penny Tompkins, James Lawley - The Magic of Metaphor (Penny Tompkins, James Lawley, March 2002)

Practical Application in NLP

Steve Andreas

Steve Andreas writes (Andreas, Steve, January, 2001):

“A MO, like accessing cues, is both a result of internal processing, and also a way to elicit it. Asking a person to say, “I won’t” rather than “I can’t,” was one of Fritz Perls, favorite ways to get people to take more responsibility for the implicit choices that they made, and feel more empowered by recognizing their ability to choose.

Sometimes changing a MO brings about a congruent change in attitude immediately. More often a client will experience incongruence. But even then it can be a very useful experiment that offers at least a glimpse of an alternate way of living in the world. The client can try it out, and find out what it would be like if it were true for him / her. The objections that arise will provide valuable information about what other aspects of the person’s beliefs need some attention in order to make the change appropriate and lasting.“

Robert Dilts: Changing Belief Systems With NLP

With Robert Dilts'9) System you can work with these kind of statements like a belief. His Belief Change Process is a systematic approach within Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) aimed at identifying, understanding, and altering limiting beliefs that hinder personal growth and achievement. Developed by Dilts, this process is designed to facilitate deep, lasting change by addressing the core beliefs that shape an individual's behavior and experiences.

Description of the Process:

- Identify the Limiting Belief:

The first step involves pinpointing the specific belief that is limiting the individual's potential. This can be done through self-reflection, questioning, or NLP techniques that bring unconscious beliefs to the surface. - Understand the Structure of the Belief:

Once identified, it is crucial to understand how the belief is constructed. This includes recognizing the sensory modalities (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.) and submodalities (brightness, volume, intensity, etc.) that support the belief. - Find the Positive Intention:

Every belief, even a limiting one, typically serves a positive intention or purpose for the individual. Identifying this intention helps in aligning the change process with the individual's core values and goals. - Dissociate from the Limiting Belief:

Techniques such as visualization, timeline therapy, or perceptual positions can help the individual dissociate from the limiting belief. This step often involves creating a mental distance from the belief to weaken its hold. - Install a New Empowering Belief:

After dissociating from the limiting belief, the process involves identifying and installing a new, empowering belief. This new belief should be congruent with the individual's values and goals and should be reinforced through repetition and emotional anchoring. - Future Pacing:

Future pacing involves imagining oneself in future scenarios where the new belief is in action. This helps in integrating the belief into the individual's daily life and ensuring that it translates into practical, positive changes. - Test and Reinforce the Change:

The final step is to test the new belief in real-life situations and reinforce it through continuous practice and adjustment. This ensures that the change is sustainable and becomes a natural part of the individual's mindset.

For in depth explanation of the process please refer to the book: “Robert Dilts - Changing Belief Systems With NLP” (Robert Dilts, February 20, 2018)

Practical Application Transactional Analysis

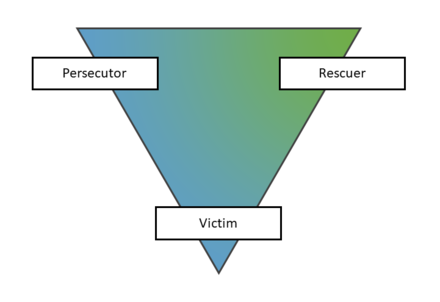

In Transactional Analysis, a modal operator (MO) of necessity, such as “must” or “should,” often signals the start of a psychological game when the implied rule or expectation is broken, as it triggers a shift into the Drama Triangle roles of Persecutor, Victim, or Rescuer.

From the point of IEMT all three roles are imprints. If you assign a certain feeling to each role you can analyse the emotional chaining.

Analyzing "I Should Not Get Angry" in Transactional Analysis Using the Drama Triangle

Transactional Analysis (TA)10) is a psychological framework developed by Eric Berne11) that explores interactions (transactions) between individuals based on three ego states: Parent, Adult, and Child. The Drama Triangle12), created by Stephen Karpman, is a model used in TA and Structural Analysis to describe dysfunctional social interactions. It consists of three roles: Persecutor, Victim, and Rescuer.

This session aims to analyze the statement “I should not get angry” using the Drama Triangle.

Initial Statement

Client: “I should not get angry.”

Identifying the Ego State

In TA, the statement “I should not get angry” likely comes from the Parent ego state, specifically the Critical Parent, which imposes rules and judgments.

Exploring the Drama Triangle

The Drama Triangle involves three roles:

- Persecutor: Blames or criticizes others.

- Victim: Feels oppressed or helpless.

- Rescuer: Tries to help or save others, often without being asked.

Let's analyze how these roles play out in the context of the statement.

Scenario Analysis

Scenario 1: Client as Victim

- Victim: The client feels they must suppress their anger, seeing themselves as powerless to express their true feelings.

- Persecutor: The internalized Critical Parent tells the client, “You should not get angry,” creating self-criticism.

- Rescuer: The client might seek external validation or someone to soothe them, reinforcing their Victim stance.

Example Dialogue:

- Client: “I should not get angry because it's wrong.”

- Therapist: “When you say 'should not,' whose voice do you hear? Is it someone from your past?”

- Client: “It sounds like my father. He always told me that anger is bad.”

Therapist's Approach:

- Help the client recognize the Critical Parent's influence.

- Encourage shifting to the Adult ego state to assess the validity of this belief.

- Explore the unmet needs behind the anger (e.g., need for respect or acknowledgment).

Scenario 2: Client as Persecutor

- Persecutor: The client directs anger inwardly, blaming themselves for feeling anger.

- Victim: The part of the client that feels hurt by this self-blame.

- Rescuer: The client might try to rationalize or suppress their feelings to avoid self-criticism.

Example Dialogue:

- Client: “I get so mad at myself for feeling angry.”

- Therapist: “It sounds like there's a harsh inner critic. What does this critic say to you?”

- Client: “It says I'm weak for getting angry.”

Therapist's Approach:

- Identify the self-critical Persecutor role.

- Facilitate self-compassion and understanding.

- Guide the client towards the Adult ego state to evaluate these self-judgments.

Scenario 3: Client as Rescuer

- Rescuer: The client tries to prevent their own anger to 'rescue' themselves or others from conflict.

- Victim: The client feels oppressed by their own or others' expectations to stay calm.

- Persecutor: Could be internal (self-criticism) or external (someone who taught them anger is unacceptable).

Example Dialogue:

- Client: “I always try to stay calm to keep the peace.”

- Therapist: “What happens if you do express your anger?”

- Client: “I fear people will reject me.”

Therapist's Approach:

- Explore the fear of rejection and its origins.

- Address the rescuing behavior and its impact on the client's well-being.

- Encourage expression of feelings in a healthy, assertive manner.

Moving Out of the Drama Triangle

To move out of the Drama Triangle, the client needs to transition from reactive roles to a more empowered stance. This involves:

- Awareness: Recognize when they are in the Drama Triangle.

- Adult Ego State: Use the Adult ego state to assess situations objectively and make conscious choices.

- Assertiveness: Express feelings and needs directly without blaming or rescuing.

Example Dialogue:

- Therapist: “How can you express your anger in a way that honors your feelings without hurting others?”

- Client: “I can say, 'I feel upset when my needs are not considered,' instead of keeping it inside.”

Conclusion

By using TA and the Drama Triangle, the client can understand the dynamics behind their statement “I should not get angry” and work towards healthier ways of managing and expressing emotions. This involves shifting from Parent or Child ego states to the Adult ego state and stepping out of the Drama Triangle roles.